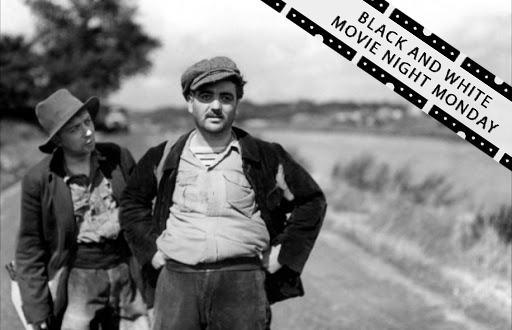

The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964) – Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

The Gospel According to St. Matthew is perhaps the most faithful adaptation of any of the four gospels ever put to film. Though Pasolini himself was an atheist, his portrayal of Jesus is blatantly straightforward, yet powerful. The film was shot with no screenplay, and its dialogue is comprised solely from the words written by Matthew in his gospel. It cuts deeper than ever. Unlike other modern interpretations of the gospel (which do a fine job attempting to capture aspects of Christ), Pasolini is more interested in recording the gospel to film without added interpretative comments or flourishes on Jesus’s life. Though this portrayal of Jesus is often labeled as Marxist, (an interpretation I don’t subscribe to), the film refrains from inflicting any viewpoints other than those recorded by Matthew in his gospel, and for that, I think we experience a more vivid, loving, and sometimes harsher view of Christ than we are used to in media such as film.

What is immediately striking about this adaptation is the reverential and humanistic approach it takes to the subject matter. It begins as a film of silence, telling the story of Jesus’s birth with sparse dialogue, but powerful images. I’m not even sure Mary and Joseph have any lines of dialogue. For the great speed at which the film travels through the account of Jesus, Pasolini often seems to pause, extending time for spiritual moments of great weight by giving screen time to human faces which are simply reacting, noticing, and embodying holy moments. Time stands still as the camera pans or cuts from one face to another — awareness seems to be the subject of these shots. It is moments like these that remind you of the universality of the language of cinema, as you forget you are watching a film with subtitles at all. I believe Pasolini is one of the filmmakers who pauses to recognize the image of God in the human face – perhaps a contradiction given Pasolini’s personal beliefs, but I stand by my statement. His approach with the camera makes the life of Jesus that much more poignant.

After Jesus’s birth, the film finds its power in dialogue-heavy scenes and montages. If the film was speaking in silence, then it shouts with words. Without minimizing the effect of the filmmaking, these sections are largely powerful because of their source material. The film recognizes the power of Jesus’s words and lets them speak for themselves. Similarly to how Pasolini extends time with close-ups, he seems to compress time with Jesus’s famous sermons – often cutting between time and location as Jesus speaks (without trimming much, if any, of the actual dialogue), which beautifully communicates the transcendent nature of the words.

Enrique Irazoqui’s great performance must also be acknowledged. He plays Jesus with a delicate balancing act between serenity and rage. This is a Jesus with deep emotions including sadness and anger at a time when other portrayals of Christ were more restrained. Christ will whisper and speak softly but also raise his voice and yell, confronting the hypocrisy and corruption of his time. (This not-so pious take on Jesus would go on to inspire Martin Scorsese, for his controversial masterpiece, The Last Temptation of Christ.) Again, nothing of this portrayal is out of left field for anyone familiar with the gospels, yet the film manages to capture the revolutionary aspect of Jesus’s teachings that is often dulled by modern culture.

In the end, The Gospel According to St. Matthew feels like a true adaptation. It’s an earnest attempt to record the life of Jesus as He was on this earth, translated faithfully to the language of cinema. If you are stirred by the words of Jesus, you will likely be stirred by this film. If you are not, you likely won’t be. “He who has ears to hear, let him hear.”